Halloween can’t arrive fast enough. And here to send chills down your spine are 20 creepy stories and haunted locations within driving distance of Cleveland. Special thanks to the book Ghosts and Legends of Northern Ohio by William G. Krejci for much of this information.

Cleveland's Creepiest Urban Legends

By Scene Staff on Sun, Oct 6, 2019 at 7:27 pm

Scroll down to view images

Helltown and the Road to Hell

PeninsulaThe history of Helltown is murky, but it seems that the town was abandoned when the National Parks Service deemed the homes as obstructions of the natural beauty of the area. Legends of a Road to Hell at Helltown claim that drivers on the road find themselves with a sudden urge to drive off the road into the Brandywine Gorge to the north. Others say that the ghosts of car accidents haunt this road, and that a ghostly hearse has been spotted at night. The road is currently closed to the public, but that doesn’t mean you can’t reach Hell on foot.

Photo via whoiskjs/Instagram

The West Branch Witch

West Branch State Park, Portage CountyThe woods in this state park are said to be haunted by a witch who appears as a woman in black. In 1960, a man named B.A. Evans discovered a small cemetary on his recently-purchased land. The plot contained seven gravestones and was surrounded by a 40-inch wall. The cemetary belonged to the Elliott family, and the graves dated back to the first half of the 19th century. One headstone bears the name “Clamenza Isadore,” the daughter of the Elliotts who died at age 17. The headstone inscription is as follows: Remeber youth as you pass by. As you are now, so once was I. As I am now, so must you be. Prepare for death and follow me.” This creepy poem has been interpreted as a witch’s hex, leading to the legend of a woman in black who chases people away from her grave.

Photo via daniel_frost_photography/Instagram

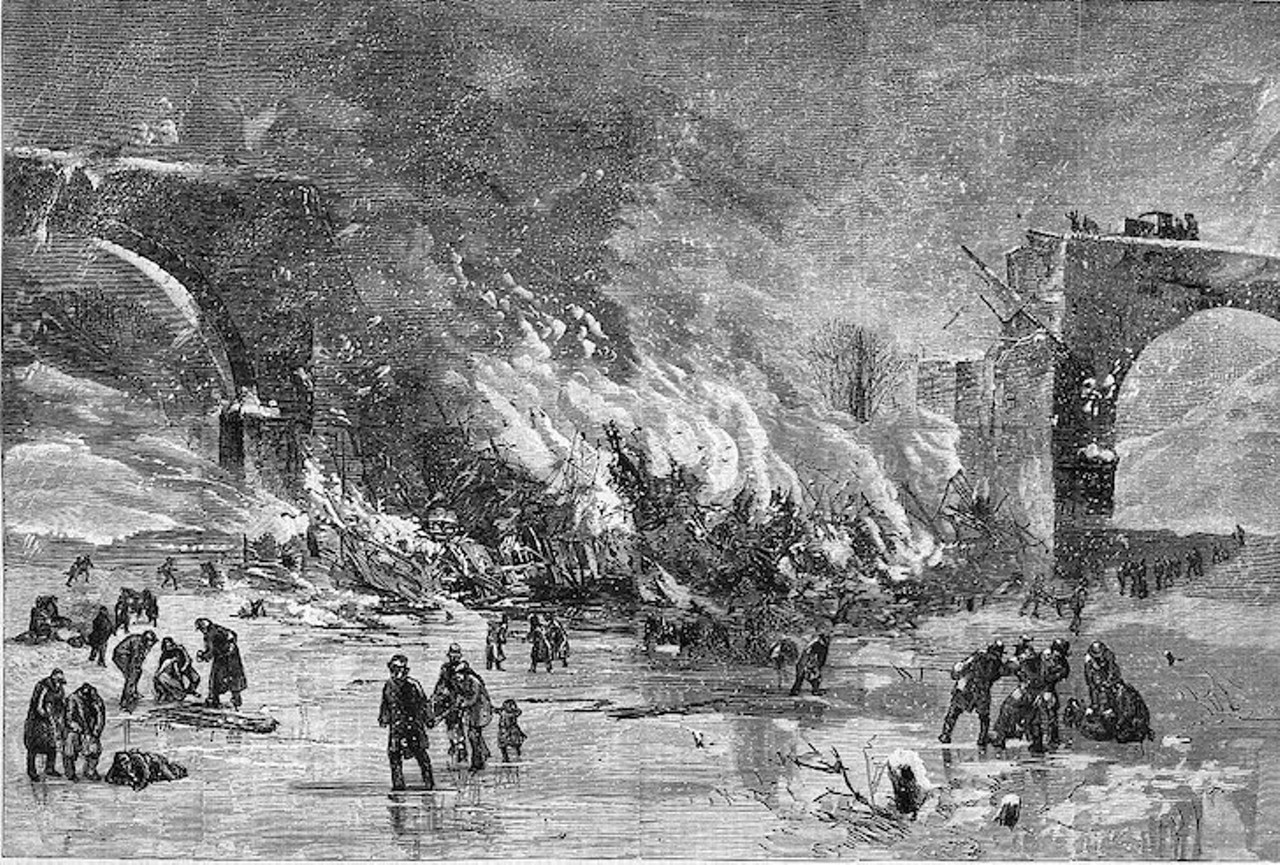

The Ashtabula Bridge Disaster

AshtabulaOn December 29, 1876, an eleven-car train with two engines and nearly 160 passengers was making its way west when a terrible snow storm began. At 7:28 p.m., the train slowed while approached Ashtabula and carefully crossed the iron bridge over the river. The bridge collapsed, and the train was plunged into the river. Those who weren’t killed in the initial fall were drowned or burned to death, as the oil from the lanterns ignited on the wooden passenger cars. 92 people died and 64 were injured. Of the dead, 48 were unrecognizable and placed in a mass grave at nearby Chestnut Grove Cemetary. But the death toll didn’t stop there: the bridge’s engineer was found dead 20 days later, his death was eventually ruled a homicide. His killer was never found. The president of the railroad that built the bridge then committed suicide a little over six years later. Ghostly figures have been spotted walking the site, with activity increasing aroun the time of the tragedy’s anniversary.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

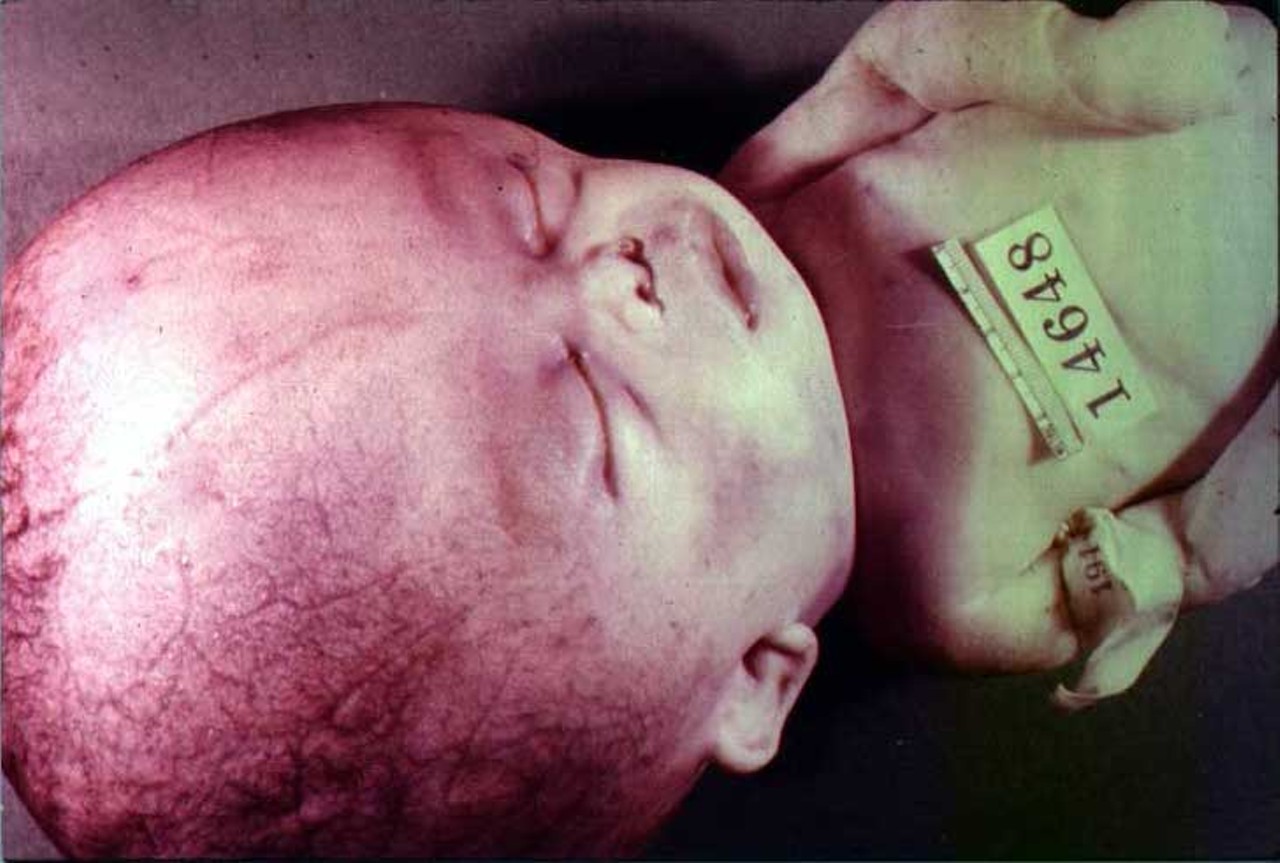

The Melon Heads

KirtlandThere was once a man named Dr. Crowe who lived off of Wisner Rd. in Kirtland. He had been stripped of his medical license because of his complete lack of ethics. He decided to open his home to orphans. Some say this was because he and his wife couldn’t conceive, others say that she did conceive, but that their child was born with hydrocephalus–– a condition that causes swelling of the brain and skull. Either way, the orphans started mysteriously developing this condition. It is thought that the evil doctor performed experiments on them, injecting fluid into their skulls. Eventually, the children revolted, killed the doctor, burned down his home, and escaped into the woods. Sightings of these strange-looking people are still reported in the area.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Gore Orphanage

Lorain CountyGore Orphanage and Gore Orphanage Rd. have a litany of horrible stories associated with their name. The main legend is that a man named Gore started an orphanage on the edge of Lorain County in the early 1800s. When the orphanage started losing money, he decided to cut his losses and locked all the children into the building, which he then set on fire. Then he collected the insurance money and left town. You can still visit the ruins today, where people have heard ghostly children crying at night.

Photo via themidnighttrainpodcast/Instagram

Crybaby Bridges and the True Story of Lizzie Shacht

Big Four Railroad Bridge, ClevelandThe legend of a crybaby bridge is a common one. Each story involves a young mother throwing her baby off the side of the bridge, where the baby’s ghostly cries linger to this day. While the Big Four Railroad bridge isn’t necessarily known as a crybaby bridge, it is the site of a real child drowning by a woman named Lizzie Shacht. Lizzie had her baby out of wedlock and threw its remains over the side of the bridge, which were later found downriver. Apparently Lizzie tied a strip of linen around the baby’s neck because she was “afraid it would start breathing again.” She was ultimately charged and convicted of murder.

Photo via Matthew O’Thompsonski/Flickr Creative Commons

Ghastly Wails at the Front Avenue River Crossing

Cleveland Waterfront RTA, West 10th St. and West 11th St.This story haunts the approximate location of the one before. The legend goes that in the early months of 1910, employees of the Big Four Railroad were repeatedly terrified by the sounds of some unseen spirit. The noise, heard every Sunday around midnight, was described as something like the agonized moan of someone in the throes of death. Two policemen investigated, but were baffled by the origin of the wailing. It was believed that the area was being haunted by the ghost of a dock worker who had been hit by a train the previous December. The source of the noise was never officially determined.

Photo via macincle/Instagram

The Witch’s Grave of Olmsted Falls

Chestnut Grove Cemetery, Olmsted TownshipThe same cemetery that houses the mass grave of the Ashtabula Bridge victims is also home to a witch’s grave. The most popular story is that a woman accused of witchcraft in the 1800s was hung from a large tree in the cemetery. Her body was then cut down and buried at the base of the tree. The creepiest version says that the witch was dismembered after being executed, with her body buried in 13 small boxes around the tree. People in the area embrace these spooky legends with a “Haunt of the Falls” display every October.

Photo via vintage.mick/Instagram

The Witch’s Ball of Valley City

Myrtle Hill Cemetery, Medina CountyThis witch’s grave is marked by a granite sphere, supposedly to prevent her from climbing back out again. The legend says that the witch killed her sons and abusive husband by dumping arsenic into the well. This may be taken from the real story of Martha Hazel Wise, who poisoned 17 of her family members with arsenic the winter of 1924-25. Supposedly, snow refuses to stick to the witch’s ball. If you touch it and it is warm, it means that the ghost of the witch is active and wandering around the cemetery.

Photo via Mat Luschek/Instagram

Chief Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Ya

Olentangy Indian CavernsThis true story tells how a great Native American leader named Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Ya (nicknamed Leatherlips) was executed for witchcraft in 1810. Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Ya was a noted chief of the Porcupine Clan of the Wyandots who became friendly with colonists after the Battle of Fallen Timbers. Another native leader named Tecumseh grew angry and sent a delegation to Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Ya with the hopes of persuading him to fight the colonists. The delegation was sent away, and fell ill and died on their way home. Tecumseh then accused Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Ya of witchcraft and ordered him to be executed by tomahawk blow. His body is believed to be buried near the Olentangy Indian Caverns. Sha-Te-Yah-Ron-Yah was the only known person to have been executed for witchcraft in Ohio.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Page 1 of 2